Adaptive Paramagnetism and Photoluminescence in Nitrogen Co-doped Mn: CdS Composite Quantum Dots

Surya Sekhar Reddy M1,2, Kishore Kumar Y B3*

1Department of Physics, JNTUA, Ananthapuramu, A.P., India.

2Department of Physics, Government Degree College (w), Madana palle, A.P., India.

3Department of Physics, Mohan Babu University (Erstwhile Sree Vidyanikethan Engineering College), Tirupati, A.P., India.

Corresponding Author E-mail: msrphd2022@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/ojc/390603

Article Received on : 15 Nov 2023

Article Accepted on : 20 Dec 2023

Article Published : 27 Dec 2023

Reviewed by: Dr. Ramesh Reddy

Second Review by: Dr. Hemanth Reddy

Final Approval by: Dr. S. A Iqbal

Manganese-doped cadmium sulfide quantum dots (QDs), co-doped with nitrogen, were synthesized using the chemical co-precipitation method (CPM). Surfactant 2-mercaptoethanol (ME) was used to efficiently regulate the size of these QDs. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses verified that the particles fell within the nano-dimension, measuring between 1-2 nm. A Rietveld analysis with X’pert high score software (XPHS) proved that these synthesized QDs contained many phases. The energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) technique confirmed the successful incorporation of both manganese and nitrogen dopants into the CdS. Ultraviolet-visible analysis (UV-Vis) demonstrated a noticeable shift towards the blue end in the energy gap, indicating the presence of a quantum-confinement effect. The photoluminescence (PL) investigations revealed a significant emission peak at λ = 634 nm, linked to the transition from 4T1 to 6A1, attributed to the incorporation of Mn2+ within the CdS core. Electron paramagnetic spectroscopy (EPR) demonstrated paramagnetic characteristics. EPR assessments of the g factor (1.995) and hyperfine splitting constant (A) values (7 mT) verified the existence of nitrogen and manganese ions in the tetrahedral positions of the CdS core. The notable alterations noticed in the magnetic and optical characteristics of the fabricated quantum dots imply promising uses in optoelectronic and magneto-luminescent applications.

KEYWORDS:Nitrogen; Paramagnetism; Photoluminescence; Quantum Dots

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Reddy M, S. S, Kumar Y. B. K. Adaptive Paramagnetism and Photoluminescence in Nitrogen, Co-doped Mn:CdS Composite Quantum Dots. Orient J Chem 2023;39(6). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Reddy M, S. S, Kumar Y. B. K. Adaptive Paramagnetism and Photoluminescence in Nitrogen, Co-doped Mn:CdS Composite Quantum Dots. Orient J Chem 2023;39(6). Available from: https://bit.ly/48d2Et0 |

Introduction

Since the 1990s, nanomaterials ranging from 1 to 100 nm in structural dimensions have emerged as a central focus in the domains of chemistry, biology, physics, and medicine [1]. These nanoparticles, or quantum dots (QDs) [2], exhibit unique properties distinct from their bulk counterparts. The alteration in their properties is chiefly attributed to two factors: the increased surface area-to-volume ratio and the quantum effects stemming from variations in particle size [3]. Quantum dots have been the subject of extensive research due to their potential applications in optoelectronics [4], solar cells [5], bio-imaging [6], and more. Their size-dependent properties, including band gap adjustments, have paved the way for innovative technologies.

Diluted-magnetic-semiconductors (DMS) are another class of nanomaterials that have garnered attention, particularly II-VI quantum dots doped with transition metals like Mn, Fe, Ni, Co, Cr, Zn, etc. [7]–[10]. These DMS exhibit fascinating optical and magnetic characteristics arising from the interaction of magnetic moments of the transition metal ions with the semiconductor lattice’s electronic bands [11]. Unlike other transition metals, manganese possesses distinctive characteristics owing to its half-filled d-orbitals [12]. These attributes play a crucial role in the formation of dimers when Mn interacts with additional dopant elements [13]. The bound magnetic polaron theory (BMP) [14] provides a framework to understand the impact of these dimers on the antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic properties exhibited by diluted magnetic semiconductor materials. The ability of manganese ions to form extra traps inside the CdS core is further demonstrated, and this leads to significant changes in the luminescence characteristics of these materials. This phenomenon gives rise to what is referred to as magnetoluminescence compounds [15].

To facilitate the understanding of DMS quantum dots (DMSQDs) [13], which are semiconducting quantum dots doped with transition metals exhibiting magnetic behavior, one must consider the profound implications of combining the distinct properties of quantum dots with the magnetic characteristics of transition metals. By incorporating the magnetic nature of DMS at the nanoscale, researchers aim to increase the efficiency of these materials in various spintronic devices [7], expecting that the small size of quantum dots will lead to extensive interactions between d electrons and sp-shelled electrons, making DMSQDs highly efficient and miniaturized spintronic devices [7].

Recent studies in the field of DMSQDs have encountered challenges related to structural instability [16]. Ganguly et al., showcased the incorporation of Mn2+ ions into CdS quantum dots [17], while Ibrahim et al., observed that Mn doping in CdS resulted in a mass loss of up to 17% at temperatures up to 720 °C [16]. Additionally, Panmad et al. reported the formation of Mn-doped CdS within a glass matrix and noted the presence of a hexagonal phase in the quantum dots [15]. However, it is important to note that the structural stability of these Mn-doped CdS quantum dots, specifically in comparison to the more stable tetrahedral phase, remains unproven. Researchers have explored the formation of secondary compounds as a means to enhance stability [18]. Nitrogen has emerged as a promising element in this regard, given its ability to exist in various ionic states (N3- with a radius of 132 pm, N3+ with a radius of 30 pm, and N5+ with a radius of 27 pm).

Incorporating nitrogen into II-VI semiconductor (CdS) particles might lead to the formation of additional compounds, suitable for both anionic and cationic replacement (due to is its small ionic radius of less than Cd2+) in compounds like CdS [19]. The pronounced electronegativity of nitrogen facilitates the generation of composite materials and secondary compounds when co-doped with d-block elements. The enhanced stability of nitrogen ions, which adopt a tetrahedral structure, compared to other phases, has been well-documented [20],[21]. Moreover, despite the fact that CdS experiences a shift in its structural phase from cubic to hexagonal, Mn2+ also assumes a stable tetrahedral phase when introduced into the CdS lattice to create diluted magnetic semiconductors [22].

The unique properties of these elements served as the driving force behind the current research endeavor, which focused on the synthesis of Mn-doped N:CdS DMSQDs. In the current study nitrogen-co-doped Mn:CdS DMSQDs were synthesized using a CPM at room temperature. This research delves into the optical, structural, and magnetic properties of these QDs, shedding light on their potential applications and contributions to the field of nanomaterials.

Methodology

A straightforward CPM was employed to synthesize the quantum dots. All chemicals utilized in the synthesis, including those for CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %), were of Sigma Aldrich AR grade and possessed a purity of 99.9%, obviating the need for additional purification steps. The cationic precursors, specifically cadmium acetate dihydrate for cadmium and manganese acetate tetrahydrate for manganese, and CN2H4S for N were utilized, while the anionic precursors comprised Na2S for sulfur. To facilitate their dissolution, Solutions with concentrations of 0.2 M for each compound were accurately concocted utilizing deionized water as the solvent, adhering to the stoichiometry, and agitated for 30 minutes.

The synthesis process is initiated with the anionic precursor, Na2S, positioned in a conical vessel and affixed to a magnetic stirring device. Afterward, the positively charged precursor, CN2H4S, was introduced gradually and agitated for half an hour. Following this, 2 ml of ME, acting as the encapsulating agent, was added incrementally and mixed for an extra 30 minutes to achieve a uniform mixture. Concurrently, the positively charged precursors were added gradually, maintaining their stoichiometric proportions, and stirred for an extended duration of 8 h to ensure the reaction’s completion. The obtained solid residues underwent several rinses with deionized water to remove potential contaminants. The purified solid residues were subsequently dried at 60 °C for a duration of 6 hrs utilizing a hot air oven, after which they were finely ground into a powder.

The Bruker D8 advance XRD from Germany was used to look at the structure. For examining its shape, the Carl FESEM03-81 was utilized. Chemical composition was figured out using the Oxford EDX with Carl FESEM. Bond energies were measured using the Agilent Cavy 360-FTIR tool. The Perkins-Elmer LAMDA950 instrument was used to study absorption over a wide range. To explore its electronic states, the JES200 CW ESR device was employed. Finally, room temperature PL was measured with the JY Fluorolog-3-11 instrument.

Results and Discussion

Elemental Analysis

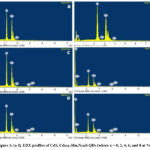

Figure 1 displays the EDX analysis of both CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %). Within all EDX patterns, a prominent presence of strong peaks corresponding to Cd and S elements is readily discernible. Notably, in Fig. 1(b) through 1(f), an additional detectable peak corresponding to both N and Mn emerges, providing strong support for the effective integration of N and Mn ions into the CdS QDs structure.

|

Figure 1: (a-f). EDX profiles of CdS, Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %). |

Structural Analysis

The pictures in Fig.2 show the XRD patterns for the prepared CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %) QDs, along with the refined XRD patterns made using the XPHS. These samples displayed clearly defined broadened peaks, signifying their presence within the nanoscale dimension.

The observed diffraction peaks matched with the crystallographic planes (331), (111), and (110), affirming that all specimens exhibit a cubic phase in accordance with JCPDS card No. 04-006-3897. Moreover, the peaks’ expansion suggested the emergence of secondary phases, with the MnS phase appearing at higher dopant concentrations (x = 4, 6, and 8 at %). The crystallographic planes of MnS (111) at 45.6º and (110) at 27.3º exhibited good agreement with the published results and JCPDS card No. 40-1288. The identification of a novel phase, S2N4, indicates the substitution of cations with nitrogen, underscoring the composite characteristics of the synthesized quantum dots.

Prior research studies conducted by Ibrahim et al., Ganguly et al., and Weichang et al., have consistently reported findings that align with our current results [16],[17]. They noted that the positions of the resulting peaks in the XRD patterns of both CdS and Mn-doped CdS remain nearly unchanged. Furthermore, Angshuman et al., noted that the X-ray diffraction profiles of CdS remained largely unchanged despite the introduction of Mn2+ ions [23]. Furthermore, Wang et al., in their investigation of Mn ion-implanted CdS films, made similar observations by noting that the positions of XRD peaks exhibit limited changes in response to Mn doping [24]. These collective findings from previous studies corroborate our own findings in the current research.

The XRD data of CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %) QDs were analyzed using the X’pert high score software, employing the pseudo-Voigt profile for peak simulation and linear interpolation for background fitting. The mean crystallite sizes, as shown in Table 1, were determined using Debye-Scherrer’s method [25] and revealed a mean size of 1.08 nm for CdS, while CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs exhibited varying sizes between 1.81 and 1.14 nm. With increasing dopant concentration, the crystalline size initially increased but subsequently decreased. The dislocation density (δ) was calculated [16] as δ = 1/D2 lines/(nm)2, where D represents the average crystallite size, as also shown in Table 1. Additionally, strain values were determined using ε = β / (4 tanθ), where ε denotes microstrain and β is the line broadening at full width at half maximum (FWHM). These strain values displayed a decreasing trend with increasing dopant concentration, signifying improved stability of the QDs. The as-prepared CdS quantum dots underwent refined X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, involving the refinement of parameters like U, V, W, symmetry parameters, and mixing coefficient (g).

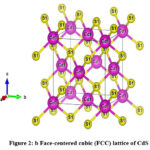

The refined structural information confirmed that the CdS QDs possess a cubic structure with lattice parameters a = b = c = 5.81799 Å, α = β = γ = 90°, space group (F -4 3 m) and a volume (V) of 196.9332 ų. The visual representation of the CdS geometrical structure was generated from the Rietveld data, as illustrated in Fig. 2b, utilizing the VESTA software.

|

Figure 2: a-f, XRD profiles of CdS, Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %). |

Table 1: Lattice strain, Dislocation density, and Crystallite sizes, of CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %)

|

Compound Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S (x %) |

From XRD |

|||

|

Crystallite size (nm) |

Dislocation density (lines/nm2 )x10-2 |

Lattice strain |

||

|

CdS |

1.08 |

85.73 |

0.14 |

|

|

x = 0 |

1.57 |

40.57 |

0.11 |

|

|

x = 2 |

1.81 |

30.52 |

0.16 |

|

|

x = 4 |

1.66 |

36.29 |

0.18 |

|

|

x = 6 |

1.22 |

67.18 |

0.18 |

|

|

x = 8 |

1.14 |

76.94 |

0.19 |

|

|

Figure 2: b. Face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice of CdS |

Morphological studies

|

Figure 3: (a-f). FESEM profiles of CdS, Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %). |

In Fig.3, the FESEM profiles of CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %) QDs are presented. These images reveal that the grains were densely packed within the samples. Remarkably, there was non-uniformity in the grain sizes, and they diminished with an increase in dopant concentration. This occurrence can be ascribed to the displacement of grain boundaries, resulting in heightened lattice strain and modifications to lattice parameters [19]. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the identified grain sizes in the doped quantum dots were smaller in comparison to those of the pristine CdS QDs.

Optical Studies

FTIR studies

Figure 4 displays the room-temperature Fourier transform infrared spectra of CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %) QDs, covering the 400-4000 cm-1 range. These spectra exhibit vibration bands corresponding to precursor and surfactant components. Vibrations below 800 cm-1 are linked to interactions involving Mn, Cd, and S, whereas the groups of an organic nature are found in the 800 to 4000 cm-1 range. Significantly, the frequency of vibrations in the 500-650 cm-1 range, linked to the Mn-S bond [16], transitioned from 640 cm-1 (in Mn:CdS) to 653 cm-1 in this instance, signifying the substitution of Mn2+ ions in CdS cationic positions. This shift, coupled with peak broadening and blue shift attributed to nitrogen, indicates the effective integration of N and Mn into the CdS core. The presence of various functional groups in the 800-4000 cm-1 range is attributed to ME, employed as a surfactant to control QDs size [26]. The FTIR analysis confirms the existence of nitrogen, manganese, and ME in the synthesized QDs.

|

Figure 4: FTIR spectra profiles of CdS, Cd0.94-x Mnx N0.06 S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %) |

UV-VIS spectra

The UV-VIS spectra captured in reflection mode as depicted in Fig. 5a showcase the comparison between CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %). These spectra revealed absorption band edge positions spanning from 470 nm to 545 nm. Initially, for CdS, the position was identified at 545 nm, gradually transitioning to 470 nm. This evident change towards the blue in the absorption band edge suggests an expanded band gap resulting from the integration of nitrogen and Mn2+ within the CdS matrix. Khan et al., reported a similar effect in their theoretical studies [27]. This shift serves as a clear indicator of the quantum confinement effect. While previous studies by Ganguly et al., reported a slight blue shift with Mn doping and Ibrahim et al., observed no significant influence of Mn on the band edge position, this present study highlights a distinct blue shift of 75 nm, attributing nitrogen’s crucial role in altering the band edge [16],[17].

For evaluating the band gap of the fabricated CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %), Tauc’s plots [28] were utilized, as depicted in Fig. 5b. The calculated positions of the band edges and corresponding band gaps are outlined in Table 2. The addition of nitrogen led to an augmentation in the CdS band gap, escalating from 2.54 to 2.67 eV. Further incorporation of Mn resulted in a subsequent increase to 4.32 eV. Previous reports by Ibrahim et al., suggested band gap values around 2.34 eV in Mn-doped CdS QDs, while Ganguly et al., reported a slight blue shift around 3.04 eV. Recently Jawad et al., reported a considerable red shift in Mn-doped CdS [29]. The apparent shift of the band gap toward the blue spectrum, as indicated in Table 2, highlights the quantum confinement effect arising from the diminished particle size within the nanoscale range. This emphasizes the influence of nitrogen in modifying the band gap.

Table 2: Band gap and Band edge positions of CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %).

|

Compound Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S (x %) |

Band edge position(nm) |

Band gap (eV) |

|

CdS |

545 |

2.54 |

|

x = 0 |

500 |

2.67 |

|

x = 2 |

480 |

4.32 |

|

x = 4 |

474 |

4.49 |

|

x = 6 |

470 |

4.50 |

|

x = 8 |

490 |

4.56 |

|

Figure 5a: Band edge positions in UV-VIS absorption spectra of CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %). |

|

Figure 5b: Tauc’s plots of CdS, Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %). |

PL studies

Room temperature photoluminescence investigations were conducted to analyze the interfaces, imperfection levels, and surface characteristics of the freshly synthesized composite QDs of N and Mn-doped CdS. Fig. 6 illustrates the PL spectra acquired at room temperature for CdS, as well as Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S (where x = 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %) QDs. Feeble emission peaks were detected across all samples at 435, 448, and 465 nm, exhibiting slight variations in their intensities. A correction has been made in the provided wavelengths for accuracy. The emergence of these peaks can be attributed to the presence of manganese ions in the lower range of the valence band. The comparatively reduced strength of the peaks suggested the confinement of ions within interstitial gaps [30]. Across all samples, the most prominent band of emission, spanning from 545 to 750 nm, exhibited a centered peak of emission at 634 nm. The rise in intensity was ascribed to the existence of N and Mn2+, enhancing the luminescence peaks’ brightness through the encouragement of hole and electron radiative recombination. The broadening of the emission peaks’ FWHM was noted with an increase in concentration. This observation suggests that the peaks became broader with the increase in the concentration of dopants. The widening of the peaks occurred due to the entrapment of dopant ions within interstitial vacancies in the bands. The highest intensity was observed for Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S (x = 2 at %), and as the concentration of Mn2+ increased further, the intensity decreased. The samples Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S (x = 6 and 8 at %) exhibited a quenching-effect [15].

The unique emission noted at the 634 nm peak is linked to the transition from the 4T1 to 6A1 energy states of the manganese ions. Neto et al., documented that this specific radiance was detected upon the integration of the Mn2+ ion as a replacement entity in the CdS lattice [31]. The slight shift towards longer wavelengths noted in the characteristic emission peak was ascribed to the reduction in the band gap, stemming from the introduction of nitrogen into the core lattice of CdS. Murali et al., in their study, noted the lack of a specific yellow peak and identified a PL peak at 700 nm, attributing it to the presence of manganese on the surface [32]. Similarly, Giribabu et al., in their research [33], highlighted a luminescence peak at 585 nm, associated with the incorporation of Mn2+ on the surface of CdS Nps. The current investigation of PL is linked to the integration of Mn2+ ions within the CdS QD core. The decline in intensity with an increase in dopant concentration implies a diminished presence of unbound ions. This phenomenon was ascribed to the generation of supplementary compounds like S2N4 and MnS, as confirmed by the XRD studies [34]. This validation indicates the composite structure of the synthesized quantum dots.

|

Figure 6: Photo luminescence spectra of CdS, Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %). |

EPR

To investigate the oxidation states of dopant ions, their occupancy positions, magnetic properties, and phase, the current study utilized EPR analysis. In Fig. 7, the EPR spectra of the synthesized CdS and Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %) quantum dots are presented. The CdS sample graph displayed no EPR signals, suggesting the lack of paramagnetic elements within pure CdS. The samples doped with nitrogen showed the elongated signal displaying a ‘g’ shift that slightly transitioned from a lower value of 2.18 to a higher value of 2.21. In most cases, nitrogen’s (I = 1) EPR spectra display a three-part signal with an inherent g = 1.995. In the present investigation, no division of the electron paramagnetic resonance signal was observed. This absence is linked to a rise in more widely dispersed imperfections, extended duration, and intensified interaction among the doped ions. No comparable reports are currently accessible for reference.

The samples doped with Mn2+, exhibited distinct sextet hyperfine splitting electron paramagnetic resonance features. The mean hyperfine-splitting constant (A) hovered at 7 mT, with a g = 1.995. Notably, the characteristic g value for manganese is 2.0 [35], and for nitrogen, it is 1.995 [36]. Consequently, the electron paramagnetic resonance signals identified in this study indicate the existence of both N and Mn2+ in the produced QDs. The marginal decrease in the g value suggests a higher ionic nature of the synthesized QDs [25]. Giri Babu et al., and Murali et al., reported Mn2+ doping on the surface of CdS with an A value of 95 G [32],[33], while Nag et al., and Jadav et al., reported the presence of Mn2+ incorporated into the tetrahedral sites of the CdS core with A = 6.9 mT. Typically, geometric phases in a tetrahedral structure display reduced energy and increased stability [37].

The formula Ns = 0.285I (∆B)2 was employed to estimate the available spins (Ns), utilizing ‘I’ (peak-to-peak signal intensity) and ‘∆B’ (peak width) values. The g = 1.995, A = 7 mT, and B0 (zero-emission magnetic field) = 338 mT parameters remain constant despite changes in Mn2+ concentration. Enhanced doping concentration elevates the signal intensity, from 1720 to 5150 a.u., signifying increased spins from 86.5 x 106 to 311 x 106, and altered paramagnetic properties in the room temperature of the prepared QDs.

In this way, the paramagnetic nature in the Mn-doped CdS composite quantum dots can be adapted by introducing nitrogen as a co-dopant.

|

Figure 7: EPR spectra of CdS, Cd0.94-xMnxN0.06S QDs (where x = 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 at %). |

Conclusion

The chemical co-precipitation method effectively produced Mn:CdS QDs doped with nitrogen. The use of ME as a surfactant efficiently regulated the nanoparticle dimensions. XRD examination confirmed the nanoscale size, approximately 1-2 nm. The Rietveld analysis through XPHS displayed the mixed composition within the produced QDs. EDX analysis confirmed the effective incorporation of nitrogen and manganese into the CdS structure. FTIR investigations provided additional evidence of the surfactant and the doped elements. UV-VIS exhibited a clear shift towards the blue end of the spectrum, indicating a decrease in particle size. The PL exhibited a distinct peak at λ = 634 nm, indicating the transition from 4T1 to 6A1, possibly due to the integration of manganese into the CdS core.EPR examination, with an A = 7 mT affirmed the existence of nitrogen and Mn2+ in the tetrahedral sites of the cubic lattice of CdS.

The successful creation of Mn:CdS quantum dots co-doped with nitrogen, featuring diverse phases, precise sizing, and desirable paramagnetic and optical characteristics, presents opportunities for their utilization in effective optoelectronic and magneto-luminescent devices across diverse technological fields.

Acknowledgment

We express our heartfelt thanks to SAIF IIT Chennai for their essential aid and prompt support in conducting the characterization procedures for this research. Their expertise and resources played a crucial role in the thorough characterization of our work, greatly contributing to the success of the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors affirm that they have no competing interests related to the publication of this research study.

References

- K. Subramani, A. Elhissi, U. Subbiah, and W. Ahmed, “Introduction to nanotechnology,” Nanobiomaterials Clin. Dent., pp. 3–18, 2019, doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-815886-9.00001-2.

- S. Tomić and N. Vukmirović, “Quantum dots,” Handb. Optoelectron. Device Model. Simul. Fundam. Mater. Nanostructures, LEDs, Amplifiers, vol. 1, pp. 419–448, 2017, doi: 10.1201/9781315152301.

- V. R. Huse, V. D. Mote, and B. N. Dole, “The Crystallographic and Optical Studies on Cobalt Doped CdS Nanoparticles,” World J. Condens. Matter Phys., vol. 03, no. 01, pp. 46–49, 2013, doi: 10.4236/wjcmp.2013.31008.

- M. Science-poland, “Stable phase CdS nanoparticles for optoelectronics : A study on surface morphology , structural and optical characterization,” vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 368–373, 2016, doi: 10.1515/msp-2016-0033.

- R. Mangiri, K. Sunil kumar, K. Subramanyam, A. Sudharani, D. A. Reddy, and R. P. Vijayalakshmi, “Enhanced solar driven hydrogen evolution rate by integrating dual co-catalysts (MoS2, SeS2) on CdS nanorods,” Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp., vol. 625, no. March, p. 126852, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.126852.

- D. Witters, B. Sun, S. Begolo, J. Rodriguez-Manzano, W. Robles, and R. F. Ismagilov, “Digital biology and chemistry,” Lab Chip, vol. 14, no. 17, pp. 3225–3232, 2014, doi: 10.1039/c4lc00248b.

- M. Yaseen, H. Ambreen, M. Zia, H. M. A. Javed, A. Mahmood, and A. Murtaza, “Study of Half Metallic Ferromagnetism and Optical Properties of Mn-Doped CdS,” J. Supercond. Nov. Magn., vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 135–141, 2021, doi: 10.1007/s10948-020-05674-0.

- A. Maria Bernadette Leena and K. Raji, “Room temperature ferromagnetism in Fe Doped CdS and cobalt doped CdS nano particles,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 8, pp. 362–370, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2019.02.124.

- S. M. Taheri, M. H. Yousefi, and A. A. Khosravi, “Tuning luminescence of 3d transition-metal doped quantum particles: Ni+2: CdS and Fe+3: CdS,” Brazilian J. Phys., vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 301–305, 2010, doi: 10.1590/S0103-97332010000300007.

- P. Kaur, S. Kumar, A. Singh, and S. M. Rao, “Improved magnetism in Cr doped ZnS nanoparticles with nitrogen co-doping synthesized using chemical co-precipitation technique,” J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron., vol. 26, no. 11, pp. 9158–9163, 2015, doi: 10.1007/s10854-015-3605-z.

- P. V. Radovanovic and D. R. Gamelin, “Electronic absorption spectroscopy of cobalt ions in diluted magnetic semiconductor quantum dots: Demonstration of an isocrystalline core/shell synthetic method,” J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 123, no. 49, pp. 12207–12214, 2001, doi: 10.1021/ja0115215.

- P. Venkatesu and K. Ravichandran, “Manganese doped cadmium sulphide (CdS: Mn) quantum particles: Topological, photoluminescence and magnetic studies,” Adv. Mater. Lett., vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 202–206, 2013, doi: 10.5185/amlett.2012.7379.

- J. M. Baruah and J. Narayan, “Dilute Magnetic Semiconducting Quantum Dots: Smart Materials for Spintronics,” Nonmagnetic Magn. Quantum Dots, 2018, doi: 10.5772/intechopen.73286.

- A. Kaminski and S. Das Sarma, “Polaron Percolation in Diluted Magnetic Semiconductors,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 88, no. 24, p. 4, 2002, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.247202.

- R. P. Panmand, S. P. Tekale, K. D. Daware, S. W. Gosavi, A. Jha, and B. B. Kale, “Characterisation of spectroscopic and magneto-optical faraday rotation in Mn2+- doped CdS quantum dots in a silicate glass,” J. Alloys Compd., vol. 817, p. 152696, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.152696.

- R. S. Ibrahim, A. A. Azab, and A. M. Mansour, “Synthesis and structural, optical, and magnetic properties of Mn-doped CdS quantum dots prepared by chemical precipitation method,” J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron., vol. 32, no. 14, pp. 19980–19990, 2021, doi: 10.1007/s10854-021-06522-0.

- A. Ganguly and S. S. Nath, “Mn-doped CdS quantum dots as sensitizers in solar cells,” Mater. Sci. Eng. B, vol. 255, no. March, p. 114532, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.mseb.2020.114532.

- I. S. Popov, N. S. Kozhevnikova, M. A. Melkozerova, A. S. Vorokh, and A. N. Enyashin, “Nitrogen-doped ZnS nanoparticles: Soft-chemical synthesis, EPR statement and quantum-chemical characterization,” Mater. Chem. Phys., vol. 215, pp. 176–182, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.04.115.

- M. Surya Sekhar Reddy, C. Sai Vandana, and Y. B. Kishore Kumar, “Room Temperature Ferromagnetism and Enhanced Band Gap Values in N Co-doped Cr: CdS Nanoparticles for Spintronic Applications,” J. Supercond. Nov. Magn., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 1243–1248, 2023, doi: 10.1007/s10948-023-06565-w.

- A. Nabi, Z. Akhtar, T. Iqbal, A. Ali, and M. A. Javid, “The electronic & magnetic properties of wurtzite Mn:CdS, Cr:CdS & Mn:Cr:CdS: First principles calculations,” J. Semicond., vol. 38, no. 7, 2017, doi: 10.1088/1674-4926/38/7/073001.

- W. Shi, F. Guo, M. Li, Y. Shi, and Y. Tang, “N-doped carbon dots/CdS hybrid photocatalyst that responds to visible/near-infrared light irradiation for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 212, no. September 2018, pp. 142–149, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.11.028.

- S. Muruganandam, G. Anbalagan, and G. Murugadoss, “Optical, electrochemical and thermal properties of Co2+-doped CdS nanoparticles using polyvinylpyrrolidone,” Appl. Nanosci., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 245–253, 2015, doi: 10.1007/s13204-014-0313-6.

- A. Nag, P. D. D Sarma, N. Pradhan, S. Das Adhikari, A. Nag, and D. D. Sarma, “Luminescence, Plasmonic and Magnetic Properties of Doped Semiconductor Nanocrystals: Current Developments and Future Prospects,” Angew. Chemie, Feb. 2017, doi: 10.1002/anie.201611526.

- M. Wang, H. Zhu, B. Liu, P. Hu, J. Pan, and X. Niu, “Bifunctional Mn-Doped N-Rich Carbon Dots with Tunable Photoluminescence and Oxidase-Mimetic Activity Enabling Bimodal Ratiometric Colorimetric/Fluorometric Detection of Nitrite,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 14, no. 39, pp. 44762–44771, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c14045.

- M. Jonnalagadda, V. B. Prasad, and A. V. Raghu, “Synthesis of composite nanopowder through Mn doped ZnS-CdS systems and its structural, optical properties,” J. Mol. Struct., vol. 1230, p. 129875, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.129875.

- A. Gadalla, M. Almokhtar, and A. N. Abouelkhir, “Effect of Mn doping on structural, optical and magnetic properties of CdS diluted magnetic semiconductor nanoparticles,” Chalcogenide Lett., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 207–218, 2018.

- Muhammad Sheraz Khan , Lijie Shi , Bingsuo Zou , “First principle calculations on electronic,magnetic and optical properties of Mn doped and N co-doped CdS,” Mater. Des., vol. 11, no. 20, pp. 5035–5040, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2020.109338

- Y.Zhou, C.Yansong, Y. Gang, F. Yaoguang,Z. Yujie,H. Yi,H. Fang, Z. Han, “An efficient method to enhance the stability of sulphide semiconductor photocatalysts: A case study of N-doped ZnS,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 1870–1876, 2015, doi: 10.1039/c4cp03736g.

- S. M. H. AL-Jawad, N. J. Imran, and K. H. Aboud, “Synthesis and characterization of Mn:CdS nanoflower thin films prepared by hydrothermal method for photocatalytic activity,” J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol., vol. 100, no. 3, pp. 423–439, 2021, doi: 10.1007/s10971-021-05656-1.

- S. M. Liu, F. Q. Liu, H. Q. Guo, Z. H. Zhang, and Z. G. Wang, “Surface states induced photoluminescence from Mn2+ doped CdS nanoparticles,” Solid State Commun., vol. 115, no. 11, pp. 615–618, 2000, doi: 10.1016/S0038-1098(00)00254-4.

- E. S. F. Neto, N. O. Dantas, N. M. B. Neto, I. Guedes, and F. Chen, “Control of luminescence emitted by Cd1-xMnxS nanocrystals in a glass matrix: X concentration and thermal annealing,” Nanotechnology, vol. 22, no. 10, 2011, doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/10/105709.

- G. Murali, D. A. Reddy, G. Giribabu, R. P. Vijayalakshmi, and R. Venugopal, “Room temperature ferromagnetism in Mn doped CdS nanowires,” J. Alloys Compd., vol. 581, pp. 849–855, 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.08.004.

- G. Giribabu, G. Murali, and R. P. Vijayalakshmi, “Structural, magnetic and optical properties of cobalt and manganese codoped CdS nanoparticles,” Mater. Lett., vol. 117, pp. 298–301, 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2013.12.024.

- S. S. R. M and K. K. Y. B, “Tunable Paramagnetism in Mn co-doped N : CdS Composite Nanoparticles,” 2023.

- D. Amaranatha Reddy, S.Sambasivam, G.Murali, B.Poornaprakash, R.P.Vijayalakshmi, Y.Aparna, B.K.Reddy, and J.L.Rao,, “Effect of Mn co-doping on the structural, optical and magnetic properties of ZnS:Cr nanoparticles,” J. Alloys Compd., vol. 537, pp. 208–215, 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.04.115.

- M. S. S. Reddy, C. S. Vandana, and Y. B. K. Kumar, “Tailoring the Inherent Magnetism of N : CdS Nanoparticles with Co 2 + Doping,” pp. 2024–2034, 2024.

- M. Kaur, V. Kumar, J. Singh, J. Datt, and R. Sharma, “Effect of Cu-N co-doping on the dielectric properties of ZnO nanoparticles,” Mater. Technol., vol. 37, no. 13, pp. 2644–2658, 2022, doi: 10.1080/10667857.2022.2055909.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.