A Comparative Study on the Interaction of Sulfonamide and Nanosulfonamide with Human Serum Albumin

G. Rezaei Behbehani

Chemistry Department, Imam Khomeini Internationl University, qazvin, Iran.

Binding parameters of the N-phenyl benzene sulfonyl hydrazide, sulfonamide, and nanosulfonamide interaction with Human serum albumin were determined by calorimetry method. The obtained binding parameters indicated that sulfonamide in the second binding sites has higher affinity for binding than the first binding sites. The binding process of sulfonamide to HSA is both enthalpy and entropy driven. The association equilibrium constants confirm that sufonamide binds to HSA with high affinity (2.2×106 and 3.86105 M-1 for first and second set of binding sites, respectively). The obtained results indicate that sulfonamide increases the HSA ani-oxidant property. Nanosulfonamide has much more affinity for HSA (3.6×106 M-1)) than sulfonamide.

KEYWORDS:Isothermal Titration Calorimetry; Sulfonamide; Nanosulfonamide; Human serum albumin; Binding sites

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Behbehani G. R. A Comparative Study on the Interaction of Sulfonamide and Nanosulfonamide with Human Serum Albumin. Orient J Chem 2012;28(4). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Behbehani G. R. A Comparative Study on the Interaction of Sulfonamide and Nanosulfonamide with Human Serum Albumin. Available from: http://www.orientjchem.org/?p=11902 |

Introduction

Physicochemical properties of nanoparticles such as their small size, large surface area, surface charge and ability to make them potential delivery systems for effective treatments. The pharmocokinetic parameters of therapeutic drugs against the diseases show limitations in their efficacy. The poor bioavailability, side effects due to the high doses administered, long treatment and the emergence of drug resistant strains are the disadvantages of ordinary drugs. The advances that nanotechnology based drug delivery systems have made in improving the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of therapeutic drugs [1-4].

Sulfonamides were the first chemical substances systematically used to treat and prevent bacterial infections in humans. Sulfonamides are bacteriostatic drugs; they work by inhibiting

the growth and multiplication of bacteria without killing them. Currently, their most common use in humans is treating urinary tract infections [5]. They are estimated to be 16-21% of annual antibiotic usage, making them the most important group of antibiotics consumed by humans [6]. Sulfonamides are compounds than contain sulfur in a SO2NH2 moiety directly attached to a benzene ring. The term “sulfa allergy” is often incorrectly applied to all adverse reactions that occur with sulfonamide-containing medications and not just to those due to hypersensitivity mechanisms. Patients who experience side effects such as nausea and vomiting may interpret this as an allergy and subsequently report that they are allergic to sulfas [7]. The binding of the sulfonamides to serum albumins, an important factor of the pharmacokinetic of these drugs, has been extensively studied by several workers. Especially regarding the extent of binding. The stoichiometry, and the influence of the chemical structure on the binding. But only little information is available on the mechanism of the binding and on the nature of the sulfonamide-albumin complex. Some workers have shown a correlation between the partition coefficients of the sulfonamides and the extent of the binding and concluded that the binding is mainly hydrophobic [8]. In this work, we compared the most comprehensive study on the interactions of solfunamide and nanosulfonamde (N-phenyl benzene sulfonyl hydrazide) with HSA for further understanding of their effects of on the stability and the structural changes of the HSA molecules.

Materials and method

Human Serum Albumin (HSA; MW=66411 gr/mol) and Tris buffer used were analytical grade with the highest purity available without any purification. Sulfonamide derivative (N-phenyl benzene sulfonyl hydrazide) was synthesized. The isothermal titration microcalorimetric experiments were performed with the four channel commercial microcalorimetric system. Sulfonamide and nanosulfonamide solutions (1612.9 µM) were injected by use of a Hamilton syringe into the calorimetric titration vessel, which contained 1.8 mL HSA (60.22 µM). Injection of sulfonamide solution into the perfusion vessel was repeated 29 times, with 10 µL per injection. The calorimetric signal was measured by a digital voltmeter that was part of a computerized recording system. The heat of each injection was calculated by the ‘‘Thermometric Digitam 3’’ software program. The heat of dilution of the sulfonamide and nanosulfonamide solutions were measured as described above except HSA was excluded. The microcalorimeter was frequently calibrated electrically during the course of the study.

Results and discussion

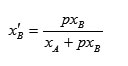

We have shown previously that the heats of the ligand + HSA interactions in the aqueous solvent mixtures, can be calculated via the following equation [9-14]:

q are the heats of sulfonamide + HSA or nanosulfonamide+HSA interactions and qmax represents the heat value upon saturation of all HSA. The parameters and are the indexes of HSA stability in the low and high sulfonamide concentrations respectively. Cooperative binding requires that the macromolecule has more than one binding site, since cooperativity results from the interactions between identical binding sites with the same ligand. If the binding of a ligand at one site increases the affinity for that ligand at another site, then the macromolecule exhibits positive cooperativity. Conversely, if the binding of a ligand at one site lowers the affinity for that ligand at another site, then the enzyme exhibits negative cooperativity. If the ligand binds at each site independently, the binding is non-cooperative. p >1 or p <1 indicate positive or negative cooperativity of a macromolecule for binding with a ligand, respectively; p = 1 indicates that the binding is non-cooperative. can be expressed as follows:

is the fraction of bound sulfonamide or nanosulfonamide to HSA, and is the fraction of unbound sulfonamide or nanosulfonamide. We can express fractions, as the sulfonamide concentrations divided by the maximum concentration of the sulfonamide or nanosulfonamide upon saturation of all HSA as follows:

[sulfonamide] is the concentration of sulfonamide after every injection and [sulfonamide]max is the maximum concentration of the sulfonamide upon saturation of all HSA. LA and LB are the relative contributions of unbound and bound sulfonamide in the heats of dilution in the absence of HSA and can be calculated from the heats of dilution of sulfonamide or nanosulfonamide in buffer, qdilut, as follows:

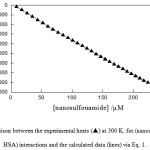

The heats of sulfonamide + HSA interactions, q, were fitted to Eq. 1 across the entire sulfonamide or nanosulfonamide compositions. In the fitting procedure, p was changed until the best agreement between the experimental and calculated data was approached (Figures 1 and 2). The high r2 value (0.999) supports the method. The binding parameters for sulfonamide + HSA interactions recovered from Eq. 1 were listed in Tables 1 and 2. The agreement between the calculated and experimental results (Figures 1 and 2) gives considerable support to the use of Eq. 1. ![]()

values for sulfonamide + HSA interactions are positive, indicating that in the low and high concentrations of the sulfonamide, the HSA structure is stabilized. These results suggest that the antioxidant property of HSA increased. p=1 indicates that the binding is non-cooperative.

|

figure 1:Comparison between the experimental heats (p) at 300 K, for (nanosulfonamide + HSA) interactions and the calculated data (lines) via Eq. 1 Click here to View figure |

|

Table 1: Comparison between the experimental heats (r) at 300 K, for (sulfonamide + HSA) interactions and the calculated data (lines) via Eq. 1. Click here to View figure |

For a set of identical and independent binding sites, a plot of

versus

should be a linear plot by a slope of 1/g and the vertical-intercept of

which g and Kd can be obtained [15-19].

Where g is the number of binding sites, Kd is the dissociation equilibrium constant, [HSA] and [sulfon] are the concentrations of HSA and sulfonamide or nanosulfonamide, respectively,

q represents the heat value at a certain ligand concentration and qmax represents the heat value upon saturation of all HSA. If q and qmax are calculated per mole of biomacromolecule then the molar enthalpy of binding for each binding site

will be

The best linear plots with the correlation coefficient value of 0.999 were obtained using amounts of -2670 and -5400 µJ (equal to -24.63, -49.81 kJmol-1) for qmax in the first and second binding sites, respectively. Dividing the qmax amounts of -24.63 kJmol-1 by g=1, and -49.81 kJmol-1 by g=4, therefore, gives

for the first binding sites,

kJmol-1 for the second binding sites.

To compare all thermodynamic parameters in metal binding process for HSA, the change in standard Gibbs free energy

should be calculated according to the equation (6), which its value can use in equation (7) for calculating the change in standard entropy

of binding process.

Where Kais the association binding constant (the inverse of the dissociation binding constant, Kd). The Ka values are obtained 22.1×105±250, 3.86×105±250 M-1 for the first and second binding sites, respectively.

The results show that there are two sets of binding sites for sulfonamide. The interaction is both enthalpy and entropy driven but the electrostatic interactions are more important than hydrophobic forces. It was found that there is 1 site in the first class of binding sites and 4 sites in the second class of binding sites. Ka values show sulfonamide in the second binding sites has higher affinity for binding than the first binding sites.

Energy of binding

for nanosulfonamide with HSA is more negative than that of sulfonamide. Therefore, the energetic interaction between nanosulfonamide and HSA has become more favorable. The affinity of nanosulfonamide is roughly twice of sulfonamide, therefore reduces the drug dosage frequency, treatment time and side effects. Ka values show that nanosulfonamid has higher affinity for binding with HSA than sulfonamide. The more effectiveness of nanosulfonamide can be attributed to its small size which, result in reducing drug toxicity, controlling time release of the drug and modification of drug pharmacokinetics and biological distribution. The positive

value (table 2) shows that nanosulfonamide (in around 30 µM of nanosulfonamide) stabilizes HSA structure and increases the anti-oxidant property of HSA. The negative

value indicates that nanosulfonamide dampened the anti-oxidant property of HSA in the high concentration domain (around 250µM of nanosulfonamide).

Table 1 Binding parameters for HSA+sulfonamide interaction. The interaction is both enthalpy and entropy-driven but the electrostatic interactions are more important than hydrophobic forces. Ka values show that sulfonamide in the second class of binding sites has higher affinity for binding than the first class of binding sites. The positive values of and indicate that the anti-oxidant property of HSA increased as a result of its interaction with sulfonamide.

Table 2 Binding parameters for HSA+nanosulfonamide interactions. The interaction is both enthalpy-driven indicating that the electrostatic interactions are dominant. Ka values show that nanosulfonamide has high affinity for binding to HSA. The positive value of indicates that the anti-oxidant property of HSA increased as a result of its interaction with nanosulfonamide. The negative value proves that nanosulfonamide dampened the anti-oxidant property of HSA in the high concentration of nanosulfonamide.

| parameters | |

| 1 | p |

| 1 | g |

| 3.6×106±650 | Ka / L.mol-1 |

| -36.43±0.12 | ∆H / kJmol-1 |

| -37.63±0.15 | ∆G / kJmol-1 |

| 0.004±0.001 | ∆S / kJmol-1K-1 |

| 2.65±0.06 | |

| -38.14±0.09 | |

Acknowledgements

The financial support of Imam Khomeini International University is gratefully acknowledged.

Reference

- Waldmann T A, in Albumin Structure, Function and Uses, eds. Rosenoer, V. M., Oratz, M. & Rothschild, M. A. (Pergamon, Oxford), 1977, 255.

- Bourdon E and Blache D, Antioxid. Redox Signal., 2001, 3, 293

- Peters T J, All About Albumin, Academic Press, San Diego, 1996.

- Watanabe H, Kragh-Hansen U, Tanase S, Nakajou K, Mitarai M, Iwao Y, Maruyama T and Otagirio M,Biochem. J., 2001, 357, 269.

- Long W J and Henderson J W, Analysis of Sulfa Drugs on Eclipse Plus C18, 2006, 5989-5436EN

- Gobel A, Thomsen A, McArdell C S, Alder A C, Giger W, Theib N, Loffler D and Ternes T A, J. Chromatogr, 2005, 1085, 179.

- Tilles S A, South Med J, 2001, 94, 817.

- Muller W E and Wollert U W E, biochemical pharmacology, 1976, 25, 1459.

- Rezaei Behbehani G, Saboury A A, Poorakbar E and Barzegar L, J Therm Anal Cal., 2010, 102, 1141.

- Rezaei Behbehani G, Saboury A A and Yahaghi E,J. Therm. Anal. Cal., 2010, 100, 283.

- Rezaei Behbehani G, Saboury A A and Sabbaghy F, Chin.J.Chem., 2011, 29, 446.

- Rezaei Behbehani G, Divsalar A, Saboury A A, Faridbod F and Ganjali M R, Chin. J. Chem., 2010, 28, 159.

- Barzegar L, Rezaei Behbehani G and Saboury A A, J Solution Chem., 2011, 40, 843.

- Rezaei Behbehani G, Saboury A A, Barzegar L, Zarean O, Abedini J and Payehghdr M, J. Therm. Anal. Cal., 2010, 101, 379.

- Rezaei Behbehani G, Saboury A A, Zarean O, Barzegar L and Ghamamy S, Chin.J.Chem. 2010, 28, 713.

- Saboury A A, Atri M S, Sanati M H and Sadeghi M, J. Therm. Anal. Cal., 2006, 83, 175.

- Rezaei Behbehani G, Saboury A A, Tahmasebi Sarvestani S, Mohebbian M, Payehghadr M and Abedini J, J Therm Anal Calorim, 2010, 102, 793

- Tazikeh E, Rezaei-Behbehani G, Saboury A A, Monajjemi M, Zafar-Mehrabian R, Ahmadi-Golsefidi M, Rajabzadeh H, Baei M T and Hasanzadeh S, J. Solution Chem., 2011, 40, 575.

- Saboury A A, Atri M S, Sanati M H, Moosavi-Movahedi A A, Hakimelahi G H and Sadeghi M, Biopolymers. 2006, 81, 120.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.